Резюме

Актуальність. Минущі порушення мозкового кровообігу не виключають можливості наявності асоційованого з ними гострого вогнищевого пошкодження тканини головного мозку. Згідно з численними дослідженнями, у 4–20 % пацієнтів із транзиторною ішемічною атакою (ТІА) інсульт розвивається в перші 90 днів, а в половини — протягом перших 48 годин після перенесеної ТІА. Нещодавні дослідження показали, що у хворих з асоційованим із ТІА гострим ішемічним вогнищем тканини головного мозку (ТІА з вогнищем) збільшується 90-денний ризик подальшого інсульту в 4 рази порівняно з пацієнтами без гострого вогнищевого ішемічного пошкодження тканини головного мозку, асоційованого з ТІА (ТІА без вогнища). Однак особливості ішемічного пошкодження тканини головного мозку в пацієнтів із різними етіологічними підтипами гострої ТІА вивчені недостатньо. Мета: описати клінічні особливості ТІА з вогнищем і без нього, вивчити причини появи і характер асоційованого з ТІА ішемічного вогнищевого ураження головного мозку в пацієнтів із різними етіологічними підтипами ТІА. Матеріали та методи. Комплексне нейровізуалізаційне, ультразвукове, лабораторне, клінічне обстеження було проведено протягом перших 24 годин із моменту розвитку ТІА 178 пацієнтам із гострою ТІА в Олександрівській міській клінічній лікарні м. Києва з вересня 2006 р. по грудень 2009 р. Результати. Згідно з даними нейровізуалізації, усі пацієнти з гострою ТІА були розподілені на 2 групи: 1-ша — ТІА з вогнищем (n = 66 — 37,0 %); 2-га — ТІА без вогнища (n = 112 — 63,0 %). Асоційоване з ТІА гостре ішемічне вогнище тканини головного мозку варіювало в діаметрі від 1,5 до 26 мм (13,4 ± 1,2 мм) і за локалізацією залежно від етіологічного підтипу ТІА (p < 0,001). Обсяг (p < 0,05) і тривалість (p < 0,001) неврологічного дефіциту при ТІА з вогнищем були істотно вищими порівняно з такими при ТІА без вогнища. Порівняно частіше ТІА з вогнищем були характерні для кардіоемболічного (39,4 %) і лакунарного етіологічних підтипів ТІА (25,8 %). Висновки. Тривалість і обсяг неврологічного дефіциту були вищими в пацієнтів із ТІА з вогнищем порівняно з хворими з ТІА без асоційованого ішемічного ушкодження головного мозку за даними нейровізуалізації і відрізнялися залежно від етіологічного підтипу ТІА.

Актуальность. Преходящие нарушения мозгового кровообращения не исключают возможности наличия ассоциированного с ними острого очагового повреждения ткани головного мозга. Согласно многочисленным исследованиям, у 4–20 % пациентов с транзиторной ишемической атакой (ТИА) инсульт развивается в первые 90 дней, а у половины — в течение первых 48 часов после перенесенной ТИА. Недавние исследования показали, что у больных с ассоциированным с ТИА острым ишемическим очагом ткани головного мозга (ТИА с очагом) увеличивается 90-дневный риск последующего инсульта в 4 раза по сравнению с пациентами без острого очагового ишемического повреждения ткани головного мозга, ассоциируемого с ТИА (ТИА без очага). Однако особенности ишемического повреждения ткани головного мозга у пациентов с разными этиологическими подтипами острой ТИА изучены недостаточно. Цель: описать клинические особенности ТИА с очагом и без него, изучить причины появления и характер ассоциированного с ТИА ишемического очага у пациентов с разными этиологическими подтипами ТИА. Материалы и методы. Комплексное нейровизуализационное, ультразвуковое, лабораторное, клиническое обследование было проведено в течение первых 24 часов с момента развития ТИА 178 пациентам с острой ТИА в Александровской городской клинической больнице г. Киева с сентября 2006 г. по декабрь 2009 г. Результаты. Согласно данным нейровизуализации, все пациенты с острой ТИА были разделены на 2 группы: 1-я — ТИА с очагом (n = 66 — 37,0 %); 2-я — ТИА без очага (n = 112 — 63,0 %). Ассоциированный с ТИА острый ишемический очаг ткани головного мозга варьировал в диаметре от 1,5 до 26 мм (13,4 ± 1,2 мм) и по локализации в зависимости от этиологического подтипа ТИА (p < 0,001). Объем (p < 0,05) и продолжительность (p < 0,001) неврологического дефицита при ТИА с очагом были существенно выше по сравнению с ТИА без очага. Сравнительно чаще ТИА с очагом были характерны для кардиоэмболического (39,4 %) и лакунарного этиологических подтипов ТИА (25,8 %). Выводы. Продолжительность и объем неврологического дефицита были выше у пациентов с ТИА с очагом в сравнении с больными с ТИА без ассоциированного ишемического повреждения головного мозга по данным нейровизуализации и отличались в зависимости от этиологического подтипа ТИА.

Background. Transient symptoms do not exclude the possibility of associated brain injury (BI). According to different authors, from 4 to 20 % of patients with transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) progress to stroke within 90 days, half — within the first 48 hours. Recent studies have shown that new ischemic BI in patients with TIA increases the risk of stroke by 4 times during next 90 days as compared to the patients with TIA without BI. Therefore, studying the causes and the nature of BI in patients with TIA is very important. The purpose of the study was to describe clinical features of TIA with BI and without it, and to study the causes and the nature of new ischemic BI using diffusion weighted magnetic-resonance imaging (DWI-MRI) in patients with different TIA subtypes (as to TOAST criteria). Materials and methods. DW-MRI has been performed within the first 24 hours for 178 patients with acute TIA treated in our hospital between September 2006 and December 2009. All these patients have also been checked clinically with Doppler ultrasound and transthoracic echocardiography. The cases were reviewed by two neurologists to establish the correlation between the diagnoses. Patients with TIA were divided into 2 groups, according to the MRI results: group 1 — TIA with new ischemic BI on DWI (n = 66 (37.0 %)), group 2 — TIA without BI (n = 112 (63.0 %)). Results. Patients with TIA and BI had a significantly greater volume (p < 0.05) and duration (p < 0.001) of neurological deficit compared with persons with TIA without BI. The new ischemic BI diameter ranged from 1.5 to 26 mm (13.4 ± 1.2 mm), and, as well as localization, it was significantly different in TIA subtypes (p < 0.001). Most often, BI were determined in cardioembolic (39.4 %) and small-vessel occlusion (25.8 %) TIA. Conclusions. The duration and volume of the neurological deficit were much higher in patients with TIA and new ischemic BI than without it, and differed depending on TIA subtypes.

Introduction

The embodiment of modern methods of neurovisualization has broadened the concept of transient ischemic attack (TIA). Transient symptoms do not exclude the possibility of associated brain injury. Despite the full regression of neurological deficit after TIA, almost 31 % of the patients exami–ned by a magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) [1–3], and nearly a half of patients examined with diffusion MRI [4–8] had the neuroanatomically relevant acute foci of ischemic brain injury (BI).

According to the latest recommendation of the ESO Writing Committee [9], patients with TIA who have BI on head imaging must be referred to the group with the high risk of the repeated stroke [10–17].

In any case, the time for secondary stroke prevention after TIA is strongly limited. We cannot assume that the irreversible pathophysiological processes have ended within this period of time and the threat of the stroke has already passed. Even after regression of neurological deficit the patient’s condition is considered as acute. “Transient” refers only to the neurological clinic and to a lesser extent related to circulatory, metabolic, biochemical, structural, and morphological changes.

This is why TIA patients need immediate hospitalization in the neurovascular center and emergency medical aid [9, 18, 19, 27–30]. The objective clinical neurological and neuroimaging evaluation of TIA will allow the neurologist to evaluate the group of patients with the high risk of the re-stroke [31, 32]. Hopefully, this will also make patients take preventive measures for treatment. However, not all practicing doctors tend to evaluate TIA as a critical state, demanding urgent help in the terms of neural-visualization development.

Materials and methods

The clinical neurologistic, Doppler ultrasound, MRI, transthoracic echocardiography diagnosis has been made for 178 patients with TIA, who went through the treatment and an examination course in the department of Neurology, Alexander City Clinical Hospital, Kyiv, between September, 2006 and December, 2009. Cases were reviewed by two stroke neurologists to establish a correlation with the diagnosis [33].

We have designed this cohort single-center TIA study to describe clinical features of TIA with and without BI to evaluate the causes and character of neuroanatomically rele–vant acute foci of ischemic brain injury on MRI/DWI-MRI for TIA patients according to different TIA subtypes (as to TOAST criteria [20]).

The diagnosis of TIA was exhibited according to the WHO standards, in case any patient appeared to have focal movement, speech, or visual impairment lasting less than 24 hours, which could be explained by possible vascular disorders. Symptoms of TIA were determined by recommendation of the Special Committee of the Advisory Board of the National Institute of Neurological, Communicative Diseases and Stroke of the United States [21].

The criteria for inclusion of patients in the study were clinical manifestations of TIA. Regression of neurological symptoms during the first 24 hours after they occur, regardless of results, consent to participate in the study was given by the patient or their legal representative. Under the le–gislation, patients were included in the study upon signing of consent agreement.

Exclusion criteria included a retinal migraine, thrombosis of the central vein of retina, retrobulbar neuritis, the debut of multiple sclerosis, focal seizures, and the possibility of Morgagni-Adams-Stokes syndrome.

Patients were hospitalized during the first 12 hours after the symptoms developed. Within 3 hours, diagnosis and treatment took place on 12 % on patients, 38 % in 6 hours, and the rest took place within 6 to 12 hours. The average time between the occurrence of the symptoms and neurological examination was 2.7 ± 0.3 (M ± m) (mediana = 2 h, mode = 1 hour).

Examination of all 178 patients with TIA was carried out using standardized charts of a single scheme. Upon receiving the patient, test reviews and interviews were carried out du–ring the acute period. On the first day, the volume of neurological deficit was measured by occurrence and again 24 hours later on the second day. Using the NIHSS scale, the duration and reversible neurological symptoms were determined.

The presence or absence of BI has been visualized through MRI and diffusion-weighted (DW) MRI during the first 24 hours, after the symptoms developed.

The functional status of the main extra- and intracranial cerebral arteries were studied by ultrasound duplex (Multigon 500M, USA) and triplex (Aloka SSD-4000, Japan) scanning using standard methods.

On suspicion of cardioembolic genesis of TIA, we have performed echocardiography of the heart (“GE Medical Systems VIVID 3”, Japan) with the conventional method. An echocardiography was performed on 40 (81.6 %) patients with atherothrombotic symptoms and 23 (53.5 %) patients with small-vessel occlusion TIA genesis. An echocardiogram of the heart was also performed on all the patients with completely undetermined subtype of the disease.

Based on the results of neurological clinic data, MRI, ultrasound Doppler studies, laboratory blood analyses, according to the similar etiological mechanisms of stroke and TIA developing, and according to the principles of the TOAST criteria [22, 23] patients have been diagnosed with the following subtypes of TIA: large-vessel occlusion or

aterotrombotic (ATR), cardioembolic (CE) and small-vessel occlusion or lacunar (LAC). In the case of undetermined genesis of TIA, or a combination of several etiologic factors, patients were placed into the group of the undetermined (UD) subtype.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the material included the use of standard methods from the evaluation between differences in comparative groups examined through nonparametric tests on IBM PC/MS by using electronic spreadsheets like Microsoft Excel 2003, and the software package Statistica 8.0 (StatSoft, USA), SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 17. To test the hypothesis of difference between group of patients, the Mann-Whitney U-test and t-test were applied. The difference was considered statistically reliable at p < 0.05.

Ethics

The local ethics committee (i.e. the Ethikkommission of Bogomolets National Medical University, Kiev, Ukraine) approved this study.

Results and discussion

The examined patients comprised 72 men (40.4 %) and 106 women (59.6 %) with their age ranging from 25 to 83 years, an average of 57.5 ± 0.9 years (table 1).

The majority of the patients were middle age (40.4 %, 45–59 years) and old age (33.1 %, 60–75). Some of the patients were of mature age (< 45 years) at 16.9 %. The smallest number of patients were elderly (> 75 years) — 9.6 %.

Despite females prevailing as the most examined patients, the percentage ratio between men and women did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) (table 2).

Only among elderly women the percentage was significantly higher (p < 0.001). The average age of men was 56.8 ± 1.5 years and did not significantly differentiate from middle-aged women — 57.9 ± 1.3 year (p > 0.05).

According to the MRI results, all patients were divi–ded into 2 groups: 1-TIA with new ischemic BI on MRI/DWI-MRI (37.0 %) and 2-without it (63.0 %).

The first group included 66 (37.0 %) patients with TIA. Twenty-four were (36.4 %) men and 42 (63.6 %) women. The average age of patients was 61.7 ± 1.6 years. The second group consisted of 112 (63.0 %) patients with TIA. Among them were 48 (42.9 %) men and 64 (57.1 %) women. They were middle age 54.9 ± 1.1 years.

Groups demonstrated the same average result of body mass index. In the first group of patients, it amounted to 28.6 ± 6.37 kg/m2 in the second group it was 27.3 ± 5.1 kg/m2, p > 0.05.

Among the first group of patients, 2.3 times of occurrences happened more often in the carotid basin (48 patients (72.7 %)) at 2.3 times (p < 0.05) by TIA records. While in the second group it was almost equal. Fifty eight patients (51.8 %) were diagnosed with TIA in the carotid basin, 54 (48.2 %) was posterior circulation TIA. Among the first group of patients, TIA more frequently occurred in the left carotid basin compared to the right (39.3 % vs 33.3 %, respectively). There is a tendency of clinical TIA state in the right carotid basin in patients without BI. However, it was in the second group of patients compared with the first, that had the silence ischemic foci not manifested clinically (p = 0.02). They were determined as a ATR disease subtype according to the neuroimaging data. This was possibly due to the localization of infarcts in the “silent” areas of the right hemisphere of the brain. All patients with retinal TIA were included in the 2nd group.

According to the imaging data, 27 patients (40.9 %) had subcortical ischemia detected in the parietal area. The frequency of detection of BI in the frontal region, basal ganglia, and cerebellum was the same (9.1 %). Four (6.1 %) patients were found to have an acute branch of ischemia in the occipital region. There were three (4.5 %) cases with the same frequency in the area of the pons and the internal capsule. Less frequently, neuroanatomically relevant acute ischemia foci were localized in the temporal region (3.0 %), thalamus (3.0 %), midbrain (1.5 %), cerebral peduncle (1.5 %) and other areas.

Measurements of lesion size plots were performed using MRI data considering the coefficient of increased tomogram. Analysis of the absolute values of cerebral infarction found that myocardial cell diameter ranged from 1.5 to 46 mm with an average of 13.45 ± 1.20 mm. Measurement of lesion size plots, were performed using MRI data considering the increased tomogram coefficient. Analysis of the absolute values of cerebral infarction found that myocardial cell diameters ranged from 1.5 to 46 mm with an average of 13.45 ± 1.20 mm. This corresponds to literature data, refe–rencing to which infarcts associated with clinical TIA differ from those in a stroke [24]. They truly are much smaller in size and, therefore, cannot result in gross neurological deficit. According to some authors, 96 % of all BI in TIA have less than 1 ml (mean 0.7 ml) in volume, while the average volume of BI in strokes is 27.3 ml [24].

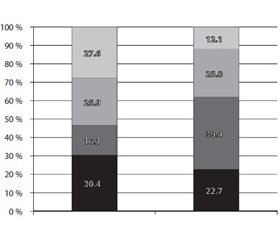

According to our data, the frequency of ischemic BI in the brain differ in patients with different subtypes TIA (fig. 1). In general, most ischemia foci were revealed from patients with CE (39.4 %), LAC (25.8 %), and ATR (22.7 %) TIA subtypes and less frequently in the case of completely UD (12.1 %) subtypes of the disease.

Each TIA subtype was characterized by features of the ratio of patients having BI and without (fig. 2). CE subtype was characterized by the largest share of patients who had BI (59.1 %), which was significantly higher compared with other subtypes (p = 0.02). More than half the patients with CE (59.1 %), and about a third of patients with ATR (30.6 %) and LAC (37 %) disease subtypes had an acute focus of ischemia according to the imaging data.

The sizes of foci were not identical in different TIA subtypes. The smallest foci occurred with the patients with LAC TIA genesis. The largest foci had those patients with CE subtype of TIA (p < 0.001). This is due to different mechanisms of ischemia progression for these subtypes of the disease. Thus, the size of foci in the TIA may vary depending on the location. Cortical and subcortical infarcts in TIA are bigger than the deeper one [24–26].

Analysis of the background level of neurological deficits in patients with different TIA subtypes showed its dependence on the presence or absence of the focus on MRI/DW-MRI. In particular, the statistically significant diffe–rences were observed between the initial volume of neurological deficits of patients with cardioembolic, aterotrombotic, and ultimately uncertain TIA subtypes with the units of damaged brain tissue compared to patients without the damaged units (p < 0.05). In cases of lacunar subtype of TIA, no significant differences from the initial neurological deficits have been detected (table 4).

Patients with CE (6.3 ± 1.9 points) and ATR (5.4 ± 1.8 points) TIA subtypes showed the highest level of background neurological deficits if the acute ischemia foci presented on MRI. It is also statistically significantly higher than the volume of neurological deficits of patients of the same subtype without BI on the MRI. Of course, the output level of neurological disorders is determined not only by pathogenic subtypes of TIA, but also by other factors including the caliber of the affected artery, localization of the ischemia focus, and its size.

Patients of all TIA subtypes with ischemia focus detected on MRI/DWI-MRI have a duration of neurological deficit different from patients without the BI (table 5).

As seen from this data, the longest duration of neurological deficit has been registered in case of provided CE and ATR subtype of TIA. Patients with LAC subtype of the disease have the shortest duration of neurological deficits. Patients of cardioembolic TIA subtype without an ischemia focus on MRI had longer period of duration of neurological disorders rather versus other versions of TIA.

Separately, we have investigated parameters of systolic blood pressure at the time of TIA in patients with different subtypes of TIA depending on the presence or absence of an acute ischemia focus according to the neurovisualization (fig. 3). This data suggests that if LAC, CE and ATR subtypes’ patients with TIA and the ischemia focus, according to the neural-visualization, had significantly higher parameters of systolic blood pressure at the time of TIA symptoms development compared to TIA patients without BI, p < 0.001. While individuals with uncertain subtype, without an ischemia focus on MRI disease, were noted to have a significant decrease of systolic blood pressure in TIA patients with ischemia focus as compared to TIA without the BI (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Despite the complete regression of neurological deficit during the first day after the TIA occurred in 37.0 % of patients, neuroanatomically relevant acute foci of ischemic brain injury has appeared on the MRI/DW-MRI. It used to occur with patients who had a CE TIA (39.4 %).

Patients with TIA and the BI had a significantly greater volume (p < 0.05) and duration (p < 0.001) of neurological deficit compared with persons with TIA without BI. The new ischemic BI diameter ranged from 1.5 to 26 mm (13.4 ± 1.2 mm) and as well as localization it was significantly different of TIA subtypes (p < 0.001).

This confirms the thesis that the transmissibility after the TIA only may be applied to neurological symptoms.

Conflicts of interests. Authors declare the absence of any conflicts of interests that might be construed to influence the results or interpretation of their manuscript.

Список литературы

1. Redgrave J.N., Schulz U.G., Briley D., Meagher T., Rothwell P.M. Presence of acute ischaemic lesions on diffusion-weighted ima–ging is associated with clinical predictors of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack // Cerebrovasc. Dis. — 2007. — 24(1). — 86-90.

2. Fazekas F., Fazekas G., Schmidt R., Kapeller P., Offenba–cher H. Magnetic resonance imaging correlates of transient cerebral ischemic attacks // Stroke. — 1996. — 27. — 607-611.

3. Davalos A. Risk of stroke in TIA with a cerebral infarct on CT // Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. — 1993. — 28(8). — 1611-1616.

4. Purroy F., Montaner J., Rovira A., Delgado P., Quintana M., Alvarez-Sabin J. Higher risk of further vascular events among transient ischemic attack patients with diffusion-weighted imaging acute ische–mic lesions // Stroke. — 2004. — 35. — 2313-2319.

5. Kidwell C.S., Alger J.R., Di Salle F. et al. Diffusion MRI in patients with transient ischemic attacks // Stroke. — 1999. — 30. — 1174-1180.

6. Coutts S.B., Simon J.E., Eliasziw M. et al. Triaging transient ischemic attack and minor stroke patients using acute magnetic resonance imaging // Ann. Neurol. — 2005. — 57. — 848-854.

7. Crisostomo R.A., Garcia M.M., Tong D.C. Detection of diffusionweighted MRI abnormalities in patients with transient ischemic attack: correlation with clinical characteristics // Stroke. — 2003. — 34. — 932-937.

8. Ay H., Koroshetz W.J., Benner T. et al. Transient ischemic attack with infarction: a unique syndrome? // Ann. Neurol. — 2005. — 57. — 679-686.

9. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) Executive Committee and the ESO Writing Committee (2008) — Guidelines for Management of Ischaemic Stroke and Transient Ischaemic Attack (http://www.eso-stroke.org/pdf/ESO08_Guidelines_ Original_english.pdf).

10. Dyken M.L., Conneally M., Haerer A.F. et al. Cooperative study of hospital frequency and character of transient ischemic attacks, I: background, organization, and clinical survey // JAMA. — 1977. — 237. — 882-886.

11. Engelter S.T., Provenzale J.M., Petrella J.R., Alberts M.J. Diffusion MR imaging and transient ischemic attacks // Stroke. — 1999. — 30. — 2762-2763.

12. Albers G.W., Caplan L.R., Easton J.D., Fayad P.B., Mohr J.P., Saver J.L., Sherman D.G. Transient Ischemic Attack — Proposal for a New Definition // NEJM. — 2002. — 347. — 1713-1716.

13. Crisostomo R.A., Garcia M.M., Tong D.C. Detection of diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities in patients with transient ischemic attack: correlation with clinical characteristics // Stroke. — 2003. — 34. — 932.

14. Douglas V.C., Johnston C.M., Elkins J., Sidney S., Gress D.R., Johnston S.C. Head computed tomography findings predict shortterm stroke risk after transient ischemic attack // Stroke. — 2003. — 34. — 2894-2898.

15. Coutts S.B., Simon J.E., Eliasziw M., Sohn C.H., Hill M.D., Barber P.A., Palumbo V., Kennedy J., Roy J., Gagnon A., Scott J.N., Buchan A.M., Demchuk A.M. Triaging transient ischemic attack and minor stroke patients using acute magnetic resonance imaging // Ann. Neurol. — 2005. — 57. — 848-54.

16. Boulanger J.M., Coutts S.B., Eliasziw M., Subramaniam S., Scott J., Demchuk A.M. Diffusion-weighted imaging-negative patients with transient ischemic attack are at risk of recurrent transient events // Stroke. — 2007. — 38(8). — 2367-9.

17. Allen C.L. Bayraktutan U. Risk factors for ischaemic stroke // International Journal of Stroke. — 2008. — 3. — 105-116.

18. Daffertshofer M., Mielke O., Pullwitt A., Felsenstein M., Hennerici M. Transient ischemic attacks are more than ministrokes // Stroke. — 2004. — 35. — 2453-2458.

19. Rothwell P.M., Giles M.F., Chandratheva A., Marquardt L., Geraghty O., Redgrave J.N., Lovelock C.E., Binney L.E., Bull L.M., Cuthbertson F.C., Welch S.J., Bosch S., Carasco-Alexander F., Silver L.E., Gutnikov S.A., Mehta Z. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (express study): A prospective population-based sequential comparison // Lancet. — 2007. — 370. — 1432-1442.

20. Goldstein L.B., Jones M.R., Matchar D.B., Edwards L.J., Hoff J., Chilukuri V., Armstrong S.B., Horner R.D. Improving the reliability of stroke subgroup classification using the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria // Stroke. — 2001. — 32. — 1091-1097.

21. Ad Hoc Committee Established by the Advisory Council for the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke. A Classification and outline of Cerebrovascular Diseases II // Stroke. — 1975. — 6. — 564-616.

22. Ad Hoc Committee on Cerebrovascular Disease of the Advisory Council of the National Institute on Neurological Disease and Blindness: a classification of and outline of Сerebrovascular Diseases // Journal of the American Academy of Neurology. — 1958. — 8. — 395-434.

23. Adams H.P.J., Bendixen B.H., Kappelle L.J. et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment // Stroke. — 1993. — 24. — 35-41.

24. Ay H., Koroshetz W.J., Benner T., Vangel M.G., Wu O., Schwamm L.H., Sorensen A.G. Transient ischemic attack with infarction: a unique syndrome? // Ann. Neurol. — 2005. — 57(5). — 679-86.

25. Kidwell C.S., Alger J.R., Di Salle F., Starkman S., Villablanca P., Bentson J., Saver J.L. Diffusion MRI in patients with transient ischemic attacks // Stroke. — 1999 Jun. — 30(6). — 1174-80.

26. Ay H., Oliveira-Filho J., Buonanno F.S., Schaefer P.W., Furie K.L., Chang Y.C., Rordorf G., Schwamm L.H., Gonzalez R.G., Koroshetz W.J. ‘Footprints’ of transient ischemic attacks: a diffusion-weighted MRI study // Cerebrovasc. Dis. — 2002. — 14(3–4). — 177-86.

27. Віничук С.М. Гострий ішемічний інсульт / Віничук С.М., Прокопів М.М. — К.: Наукова думка, 2006. — 286 с.

28. Міщенко Т.С., Здесенко І.В., Міщенко В.М. Транзиторні ішемічні атаки. Сучасні аспекти діагностики, лікування та профілактики // Міжнародний неврологічний журнал. — 2017. — № 1(87). — С. 25-32.

29. Cучасні принципи діагностики та лікування хворих із гострим ішемічним інсультом та ТІА // http://www.mif-ua.com/archive/article/35211

30. Fartushna O.Y. Emergency therapeutic approach as a secon–dary prevention of an acute ischemic stroke in patients with TIA / Fartushna O.Y. / XX World Neurological Congress, 12–17.11.2011. — Marrakesh, Morocco, 2011. — P. 167.

31. Фартушна О.Є. Транзиторні ішемічні атаки / О.Є. Фартушна, С.М. Віничук. — К.: ВД «Авіцена», 2014. — 216 с.

32. Fartushna O.Y. TIA with new ischemic lesion: clinical features and stroke risk for patients with different TIA subtypes / Fartush–na O.Y. / 2012 American Neurological Association Annual Meeting, 07–09.10.2012. — Boston, USA, 2012. — P. 36-37.

33. Фартушна О.Є. Патогенетичні підтипи транзиторних ішемічних атак: особливості неврологічної клініки, гемодинаміки та лікування [Текст]: Дис… канд. мед. наук: спец. 14.01.15 / Фартушна Олена Євгенівна; Нац. мед. ун-т ім. О.О. Богомольця. — К., 2012. — 217 с.

/15-1.jpg)

/15-2.jpg)

/16-1.jpg )

/16-3.jpg)

/16-2.jpg )