Международный эндокринологический журнал Том 18, №2, 2022

Вернуться к номеру

Гіперкортицизм на тлі реабілітації після COVID-19 (клінічний випадок)

Авторы: Kravchenko V. (1), Rakov O. (1), Slipachuk L.V. (2)

(1) — State Institution “V.P. Komisarenko Institute of Endocrinology and Metabolism of the NAMS of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine

(2) — Bohomolets National Medical University, Kyiv, Ukraine

Рубрики: Эндокринология

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

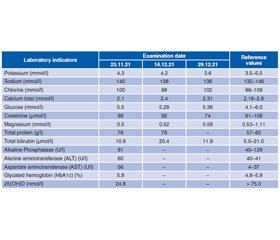

Ураження легеневої тканини належить до переважних ускладнень вірусного захворювання COVID-19. Також описані ускладнення з боку інших органів, у тому числі з боку ендокринних залоз. Повідомляється про ураження надниркових залоз зі зниженням їх функції на тлі COVID-19. Декілька досліджень автопсії надниркових залоз у пацієнтів виявили судинний тромбоз, ліпідну дегенерацію коркового шару, ішемічний некроз, паренхіматозні інфаркти та інші ураження, що призводять до зниження функції надниркових залоз. Також можливий центральний механізм дисфункції надниркових залоз унаслідок крововиливу та некрозу гіпофіза. У статті подано рідкісний випадок розвитку гіперкортицизму у молодої жінки після одужання від COVID-19. Зважаючи на високий рівень АКТГ (157 і 122 пг/мл), негативний нічний дексаметазоновий тесту і високі 24-годинні показники екскреції вільного (добового) кортизолу з сечею, автори попередньо запідозрили хворобу Кушинга. Хромогранін А був у межах норми — 21,35 (референтне значення < 100). Інші тести показали підвищений рівень дигідротестостерону — 780,6 пг/мл (референтні значення 24–368 пг/мл). Рівні інших досліджених гормонів передньої частки гіпофіза були в межах норми. Згідно з клінічними рекомендаціями, препаратом вибору для короткочасного лікування цього захворювання є інгібітори стероїдогенезу — кетоконазол. Ефективність такої схеми лікування раніше була доведена іншими дослідниками. У нашому випадку призначали кетоконазол у дозі 400 мг 2 рази на добу та каберголін (достинекс) у початковій дозі 1 мг на добу. Зважаючи на низький рівень вітаміну D у сироватці крові, рекомендовано продовжувати прийом вітаміну D у дозі 4000 МО на добу. Рекомендовано через 2 місяці контролювати лабораторні показники крові — кортизол сироватки, АКТГ, АСТ, АЛТ, електроліти, 25(OH)D, рівень глюкози в крові та визначитися з подальшою тактикою ведення хворої.

Damage to the lung tissue is a predominant complication of the viral disease COVID-19. Recently, there have been complications from other organs, including highly vascularized endocrine glands. Regarding the adrenal glands, there are reports of their damage with a decrease in their function. Сhanging the function of the adrenal glands (AG) in patients with or after COVID-19 is important. A few adrenal autopsy studies in patients have revealed vascular thrombosis, cortical lipid degeneration, ischemic necrosis, parenchymal infarcts, and other lesions leading to a decrease in AG function. The central mechanism of adrenal dysfunction through hemorrhage and necrosis of the pituitary gland is also possible. This paper presents a rare case of the development of hypercortisolism in a young woman after recovering from COVID-19. Based on high ACTH levels (157 and 122 pg/ml), a negative nocturnal dexamethasone test, and high 24-hour urinary free (daily) cortisol excretion rates, we tentatively suspected Cushing’s disease. Chromogranin A was within the normal range of 21.35 (reference value < 100). Other tests showed an elevated dihydrotestosterone level of 780.6 pg/ml (reference values 24–368 pg/ml). The levels of other anterior pituitary hormones tested were within the normal range. According to clinical guidelines, the drug of choice for the short-term treatment of this disease is steroidogenesis inhibitors — ketoconazole. The effectiveness of such a treatment regimen was previously brought to light by others. In our case, ketoconazole was prescribed at a dose of 400 mg 2 times a day and cabergoline (dostinex) at an initial dose of 1 mg per day. Given the low levels of vitamin D in the blood serum, it was recommended to continue taking vitamin D at a dose of 4000 IU per day. It was recommended to control blood laboratory parameters — serum cortisol, ACTH, AST, ALT, electrolytes, 25(OH)D, blood glucose level after 2 months and decide on further tactics for managing the patient.

синдром Кушинга, гіперкортицизм, COVID-19, лікування, клінічний випадок

Cushing’s syndrome; hypercortisolism; COVID-19; treatment; case report

Abbrevations

Introduction

Case description

/55.jpg)

Discussion

Conclusions

- WHO. Weekly operational update on COVID-19 — 22 February 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-operational-update-on-covid-19-22-february-2022.

- Ding Y., Wang H., Shen H., Li Z., Geng J., Han H., Cai J., et al. The clinical pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a report from China. J. Pathol. 2003. 200. 282-289. doi: 10.1002/path.1440.

- Guo Y., Korteweg C., McNutt M.A., Gu J. Pathogenetic mechanisms of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Virus Res. 2008. 133. 4-12. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.022.

- Yang J.K., Feng Y., Yuan M.Y., et al. Plasma glucose levels and diabetes are independent predictors for mortality and morbidity in patients with SARS. Diabet Med. 2006. 23(6). 623-628. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01861.x.

- Gupta R., Ghosh A., Singh A.K., Misra A. Clinical conside–rations for patients with diabetes in times of COVID-19 epidemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020. 14. 211-212. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002.

- Ippolito S., Dentali F., Tanda M.L. SARS-CoV-2: a potential trigger for subacute thyroiditis? Insights from a case report. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2020. 43(8). 1171-1172. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01312-7.

- Asfuroglu Kalkan E., Ates I. A case of subacute thyroiditis associated with Covid-19 infection. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2020. 43(8). 1173-1174. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01316-3.

- Lania A., Sandri M.T., Cellini M., et al. Thyrotoxicosis in patients with COVID-19: the THYRCOV study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020. 183(4). 381-387. doi: 10.1530/eje-20-0335.

- Ye Z., Wang Y., Colunga-Lozano L.E., et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in COVID-19 based on evidence for COVID-19, other coronavirus infections, influenza, community-acquired pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2020. 192(27). E756-E767. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200645.

- Ledford H. Coronavirus breakthrough: dexamethasone is first drug shown to save lives. Nature. 2020. 582(7813). 469.

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P., Lim W.S., et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 — Preliminary Report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. 384(8). 693-704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436.

- Freire Santana M., Borba M.G.S., Baía-da-Silva D.C., et al. Case report: adrenal pathology findings in severe COVID-19: an autopsy study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020. 103(4). 1604-1607. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0787.

- Iuga A.C., Marboe C.C., Yilmaz M.M., Lefkowitch J.H., Gauran C., Lagana S.M. Adrenal vascular changes in COVID-19 autopsies. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2020. 144(10). 1159-1160. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0248-LE.

- Frankel M., Feldman I., Levine M., Frank Y., Bogot N.R., Benjaminov O., Kurd R., Breuer G.S., Munter G. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in Coronavirus disease 2019 patient: a case report. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020. 105(12). dgaa487. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa487.

- Leow M.K., Kwek D.S., Ng A.W., Ong K.C., Kaw G.J., Lee L.S. Hypocortisolism in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 2005. 63. 197-202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02325.x.

- Hanley B., Naresh K.N., Roufosse C., et al. Histopathological findings and viral tropism in UK patients with severe fatal COVID-19: a post-mortem study. Lancet Microbe. 2020. 1. e245-e253. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30115-4.

- Ragnarsson O., Olsson D.S., Chantzichristos D., Papakokkinou E., Dahlqvist P., Segerstedt E., Olsson T., et al. The incidence of Cushing’s disease: a nationwide Swedish study. Pituitary. 2019. 22. 179-186. doi: 10.1007/s11102-019-00951-1.

- Newell-Pric Je., Nieman L.K., Reincke M., Tabarin A. Endocrinology In The Time Of COVID-19: Management of Cushing’s syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2020. 183 (1). G1-G7. doi: 10.1530 / EJE-20-0352.

- Moncet D., Morando D.J., Pitoia F., Katz S.B., Rossi M.A., Bruno O.D. Ketoconazole therapy: an efficacious alternative to achieve eucortisolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome. Medicina (Buenos Aires). 2007. 67. 26-31.

- Blevins L.S., Sanai N., Kunwar S., Devin J.K. An approach to the management of patients with residual Cushing’s disease. J. Neurooncol. 2009. 94(3). 313-319. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9888-2.

- Lacroix A., Feelders R.A., Stratakis C.A., Nieman L.K. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet. 2015. 29. 386. 913-27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61375-1.

- Pivonello R., Isidori A.M., De Martino M.C., Newell-Price J., Biller B.M., Colao A. Complications of Cushing’s syndrome: state of the art. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016. 4. 611-629. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00086-3.

- Gu J., Gong E., Zhang B., Zheng J., Gao Z., Zhong Y., Zou W., et al. Multiple organ infection and the pathogenesis of SARS. J. Exp. Med. 2005. 202. 415-424. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050828.

/56.jpg)