Международный эндокринологический журнал Том 18, №3, 2022

Вернуться к номеру

Дослідження валідності та надійності шкали фатальних наслідків у хворих на цукровий діабет 2-го типу в Туреччині Виправлено: Міжнародний ендокринологічний журнал — International Journal of Endocrinology (Ukraine). 2022;18(8):440-445. doi: 10.22141/2224-0721.18.8.2022.1223

Авторы: E. Kavuran (1), E. Yildiz (2)

(1) — Department of Nursing Fundamentals, Nursing Faculty, Ataturk University, Erzurum, Turkey )Central Campus-Yakutiye-Erzurum, Turkey

(2) — Department of Public Health Nursing, Nursing Faculty, Ataturk University, Erzurum, Turkey

Рубрики: Эндокринология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

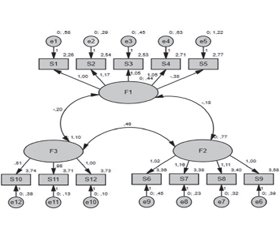

Актуальність. Туреччина є однією з країн з найвищою поширеністю цукрового діабету (ЦД) в Європі, адже приблизно у кожного сьомого дорослого діагностований ЦД. До 2035 року в Туреччині прогнозується найбільша кількість людей з ЦД 2-го типу в Європі — майже 12 мільйонів. Рівень смертності зростає зі збільшенням поширеності ЦД 2-го типу, особливо серед населення молодших вікових груп. При цьому половина випадків смерті припадає на осіб віком молодше за 60 років. Психічний стан пацієнтів із хронічними захворюваннями, такими як ЦД, може впливати на перебіг хвороби та здійснення самоконтролю. Належне лікування ЦД сприяє досягненню компенсації хвороби, але при цьому також слід брати до уваги можливість фатальних наслідків на тлі ЦД. Мета: дослідити надійність та валідність турецької версії шкали фатальних наслідків у хворих на цукровий діабет (DFS), розробленої Egede. Матеріали та методи. Проведено методологічне дослідження. Опитування за допомогою шкали проведено загалом 139 пацієнтам з ЦД 2-го типу. Оцінено зміст і конструктивну валідність шкали. Валідність шкали оцінювалася за допомогою підтверджувального факторного аналізу (CFA), а надійність оцінювалася з точки зору внутрішньої узгодженості. Результати. 54,7 % учасників тестування становили чоловіки, 73,4 % одружені, 54 % мали інше захворювання, 18 % були випускниками середньої школи, середній вік 50,20 ± 16,82 року, середня тривалість ЦД становила 19,31 ± 14,25 року, а середній рівень глікованого гемоглобіну (HbA1c) — 7,06 ± 0,65 %. Установлено, що показник Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) адекватності розміру вибірки становив 0,770. Це вказує на відповідний розмір, а значення хі-квадрат становило 1078,402. При виключенні п’ятого пункту з дослідження та повторному аналізі коефіцієнт КМО становив 0,802, а значення хі-квадрат — 1020,244, p = 0,000. Значення Cronbach’s alpha досягло 0,806, що вказує на добру внутрішню консистенцію. Значення Cronbach’s alpha інших підшкал також були на дуже доброму рівні. Висновки. Проведене дослідження показало, що DFS є валідною та надійною шкалою для турецької популяції. Шкала DFS-T цілком придатна для оцінки фатальних наслідків серед хворих на цукровий діабет в Туреччині.

Background. Turkey is one of the them that has the highest prevalence in Europe, with about one in every seven adults diagnosed diabetes mellitus. By 2035, Turkey will have the highest number of people with type 2 diabetes in Europe, at almost 12 million. Mortality rates have increased with the increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes, especially in the younger population, such that half of the deaths come from those under sixty. The beliefs and mental state of patients with chronic illnesses like diabetes can affect disease outcomes and the patients’ self-management. Self-care and diabetes medications are important components in improving the disease outcome, though many studies have shown that these activities can be negatively related to fatalism about the disease state. The aim of this study was to investigate the reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Diabetes Fatalism Scale (DFS), which was developed by Egede. Materials and methods. This was a methodological study. The scales were administered to a total of 139 patients with type 2 diabetes. The content and construct validity of the scale were assessed. The construct validity was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and the reliability was assessed in terms of internal consistency. Results. In terms of the population tested, 54.7 % of the participants were men, 73.4 % were married, 54 % had another disease, 18 % were high school graduates, the average age was 50.20 ± 16.82 years, the average duration of diabetes was 19.31 ± 14.25, and mean glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 7.06 ± 0.65 %. It was found that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling-size adequacy was 0.770, indicating an adequate size, and the chi-square value was 1078.402. When the fifth item was excluded from the study and the analysis was repeated, the KMO coefficient was 0.802 and the chi-square value was 1020.244, p = 0.000. The Cronbach’s alpha value reached 0.806, indicating a good internal consistency. The Cronbach’s alpha values of the other subscales also seemed to be at a very good level. Conclusions. Our study showed that the DFS is a valid and reliable scale for the Turkish society. DFS-T is a suitable scale for health professionals to use to assess the fatalism of diabetic patients in Turkey.

цукровий діабет 2-го типу; фатальні випадки; шкала DFS; надійність; валідність

type 2 diabetes; fatalism; nursing; reliability; validity

Introduction

Materials and methods

Sample

Linguistic Validity and Assessment of the Data

Content Validity

Measurement Instruments

Data Analysis

Ethical Consideration

Results

Exploratory Factor Analysis

/8_2.jpg)

Discussion

Conclusions

- Wu H., Patterson C.C., Zhang X., Ghani R.B.A., Magliano D.J., Boyko E.J., Ogle G.D., Luk A.O.Y. Worldwide estimates of incidence of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents in 2021. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022. 185. 109785. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109785.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 10th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2021.

- Lange L.J., Piette J.D. Personal models for diabetes in context and patients’ health status. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006. 29(3). 239-253. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9049-4.

- Funnell M.M., Brown T.L., Childs B.P., Haas L.B., Hosey G.M., Jensen B., et al. National standards for diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2021. 35(1). 101-108. doi: 10. 2337/dc12-s101.

- Walker R., Smalls B. Effect of diabetes fatalism on medication adherence and self-care behaviors in adults with diabetes. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2012. 34(6). 598-603. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.

- Franklin M.D., Schlundt D.G., McClellan L.H., Kinebrew T., Sheats J., Belue R., Brown A., et al. Religious fatalism and its association with health behaviors and outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007. 31(6). 563-72. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.6.563.

- Niederdeppe J., Levy A.G. Fatalistic beliefs about cancer prevention and three prevention behaviors. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2007. 16(5). 998-1003. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0608.

- Unantenne N., Warren N., Canaway R., Manderson L. The strength to cope: spirituality and faith in chronic disease. J. Relig. Health. 2013. 52(4). 1147-61. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9554-9.

- Nabolsi M.M., Carson A.M. Spirituality, illness and personal responsibility: the experience of Jordanian Muslim men with coronary artery disease. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2011. 25(4). 716-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00882.x.

- Omu O., Al-Obaidi S., Reynolds F. Religious faith and psychosocial adaptation among stroke patients in Kuwait: a mixed method study. J. Relig. Health. 2014. 53(2). 538-51. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9662-1.

- Doumit M.A., Huijer H.A., Kelley J.H., El Saghir N., Nassar N. Coping with breast cancer: a phenomenological study. Cancer Nurs. 2010. 33(2). E33-9. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c5d70f.

- Egede L.E., Ellis C. Development and psychometric properties of the 12-item diabetes fatalism scale. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010. 25(1). 61-6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1168-5.

- Egede L.E., Bonadonna R.J. Diabetes self-management in African Americans: an exploration of the role of fatalism. Diabetes Educ. 2003. 29(1). 105-15. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900115. PMID: 12632689.

- Walker R.J., Smalls B.L., Hernandez-Tejada M.A., Campbell J.A., Davis K.S., Egede L.E. Effect of diabetes fatalism on medication adherence and self-care behaviors in adults with diabetes. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2012. 34(6). 598-603. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.07.005.

- Aycan Z., Kanungo R.N. The effects of social culture on organizational culture and human resources practices. Management, leadership and human resources applications in Turkey. 2000.

- Patel N.R., Chew-Graham C., Bundy C., Kennedy A., Blickem C., Reeves D. Illness beliefs and the sociocultural context of diabetes self-management in British South Asians: A mixed methods study. BMC Family Practice. 2015. 16. 58. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0269-y.

- Abdoli S., Ashktorab T., Ahmadi F., Parvizy S., Dunning T. Religion, faith and the empowerment process: Stories of Iranian people with diabetes. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2011. 17(3). 289-298. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01937.x.

- Carkoglu A., Kalaycıoglu E. Devoutness in Turkey: An International Comparison. Retrieved June 2, 2014. Available from: http://research.sabanciuniv.edu/13119/1/Rapor_Kamu-dindarl %C4 %B1k.pdf.

- Sukkarieh-Haraty O., Egede L.E., Abi Kharma J., Bassil M. Diabetes fatalism and its emotional distress subscale are independent predictors of glycemic control among Lebanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Ethn. Health. 2019. 24(7). 767-778. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2017.1373075.

- Lawrence Cohn L., Esparza-Del Villar O. Fatalism and health behavior: a meta-analytic review. Report number: Colección Reportes Técnicos de Investigación. 2015, Serie ICSA, Vol. 26. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.10843.98085.

/8.jpg)

/9.jpg)