Артеріальна гіпертензія (АГ) є найбільш поширеним захворюванням системи кровообігу, а також одним з найголовніших факторів ризику розвитку серцево-судинних захворювань (ССЗ). Практично 35 % населення України мають підвищений артеріальний тиск (АТ), який часто поєднується з іншими класичними факторами серцево-судинного (СС) ризику, що зумовлює високу частоту ускладнень з боку мозку, серця та нирок. Перебіг АГ залежить від багатьох зовнішніх і внутрішніх причин, значно погіршуючись за наявності коморбідної патології. Незаперечним є негативний вплив подій військового часу на перебіг таких поширених неінфекційних хронічних захворювань, як АГ і цукровий діабет (ЦД) 2-го типу. Така коморбідність і в мирний час чинить вкрай негативний вплив на прогноз пацієнтів, збільшуючи смертність серед осіб з АГ і ЦД 2-го типу в 4–7 разів порівняно з особами, які цих захворювань не мають. В основі синергічного погіршення прогнозу пацієнтів з АГ та ЦД 2-го типу лежить спільність патогенетичних рис цих, здавалося б, не споріднених захворювань. Однак обом захворюванням притаманні активація симпатоадреналової (САС) та ренін-ангіотензин-альдостеронової (РААС) систем, затримка натрію і води нирками, активація оксидативного стресу, наявність ознак системного запалення низької градації, розвиток ендотеліальної дисфункції, збільшення судинної реактивності. В умовах інсулінорезистентності, яка є основою розвитку ЦД 2-го типу і водночас однією з характерних рис АГ, порушується синтез та біодоступність оксиду азоту, збільшується чутливість судин до вазопресорних агентів, зокрема до ангіотензину ІІ, активність мітогенактивованої протеїнкінази, синтез ендотеліну-1, проліферація гладком’язових клітин, порушення авторегуляції судинного тонусу.

Надзвичайно гостро проблема ведення пацієнтів з АГ і ЦД 2-го типу постала з початком війни в Україні. У перший місяць війни головною проблемою в масштабах усієї країни стала гостра нестача антигіпертензивних та цукрознижувальних препаратів, що виникла переважно внаслідок логістичних проблем. Саме в цей період у багатьох пацієнтів з АГ і ЦД 2-го типу значно погіршився контроль АТ та глікемії, які навіть за мирного часу в нашій країні були вкрай незадовільні [1]. Втрата контролю над такими факторами СС-ризику, як АТ, глюкоза крові, холестерин ліпопротеїнів низької щільності (ХС ЛПНЩ), з великою ймовірністю має як короткострокові, так і віддалені наслідки щодо розвитку СС-катастроф, а також ниркового ураження.

Упродовж місяця на підконтрольних Україні територіях вдалося повністю відновити адекватне забезпечення пацієнтів лікарськими засобами, зокрема антигіпертензивними та цукрознижувальними препаратами. Це однозначно сприяло покращенню лікування пацієнтів з хронічними неінфекційними захворюваннями, однак на перший план вийшов негативний вплив стресу на перебіг АГ і ЦД 2-го типу.

Загалом в умовах воєнного конфлікту пацієнти із АГ і ЦД 2-го типу стикаються із цілою низкою проблем:

— кардинальна зміна способу життя та необхідність швидкої адаптації до нових умов;

— зміна звичок: зниження рівня фізичної активності, яка обмежена через часткове зменшення простору пересування та погіршення безпеки; відновлення паління та збільшення споживання алкоголю;

— обмежений доступ до харчування з ризиком гіпоглікемій і коливань рівня глюкози крові;

— монотонні будні та щоденні труднощі також можуть призвести до втрати здатності реально оцінювати рівень безпеки та стан свого здоров’я;

— негативний вплив стресу на контроль глікемії, АТ, ХС ЛПНЩ;

— несвоєчасна діагностика, яка збільшує ризик розвитку тяжких кардіальних, церебральних та ниркових ускладнень АГ і ЦД.

Безперечно, під час будь-яких катастроф і криз (у тому числі під час війни) для пацієнтів із порушеннями вуглеводного обміну (зокрема, із ЦД 2-го типу) завжди існують суттєві ризики. Вони можуть бути пов’язані як із гіперглікемією (труднощі з продовженням інсулінотерапії, стреси через різкі зміни життєвого середовища, споживання висококалорійної/високовуглеводної їжі), так і з гіпоглікемією (недотримання дієти та/або пропуски прийомів їжі, відсутність можливості контролю рівня глюкози крові, помилкове сприйняття симптомів гіпоглікемії як симптомів тривоги, страху та стресу під час воєнного стану). На все це треба обов’язково зважати й пояснювати пацієнтам, як вони можуть своєчасно диференціювати ці стани.

Важливо зазначити, що в сучасних настановах [16] стрес розглядається як модифікатор ризику ССЗ. Це означає, що у разі сумнівів щодо визначення категорії ризику ССЗ наявність стресорних факторів може перекваліфікувати особу в категорію більш високого ризику. Варто пам’ятати, що стратифікація ризику розвитку ССЗ у пацієнтів з ЦД має певні особливості — для них не застосовується шкала SCORE2. Для оцінки серцево-судинного ризику у пацієнтів з ЦД враховується тривалість захворювання, наявність факторів ризику та ураження органів-мішеней, а також, як і в загальній популяції, наявність атеросклеротичних ССЗ (табл. 1).

/39.jpg)

Гострий та хронічний стрес визнано чинником СС-ризику за рахунок цілої низки патогенетичних зрушень, які він викликає. В умовах гострого стресу це активація симпатичної та зниження активності парасимпатичної нервової системи з транзиторним підвищенням АТ і частоти серцевих скорочень, транзиторна дисфункція ендотелію; підвищення коагуляційного потенціалу крові; гіперглікемія та гіперліпідемія [13]. В умовах дистресу на тлі дисбалансу автономної нервової системи акценти зміщуються в бік активації гіпофізарно-тиреоїдно-наднирникової осі з надлишковою продукцією кортизолу. Наслідком цього є стабільне підвищення АТ, поглиблення порушень вуглеводного та ліпідного метаболізму, що зумовлює подальше потенціювання атеросклеротичного процесу [2]. У проспективному дослідженні MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) тривалістю в середньому 6,5 року було продемонстровано, що більш високі рівні екскреції із сечею стресових гормонів (адреналін, норадреналін, допамін, кортизол) асоційовані з підвищеним ризиком розвитку АГ, натомість лише рівень кортизолу в сечі був предиктором розвитку ССЗ [10].

В умовах дистресу спостерігається значне, у 2–3 рази, зростання ризику ССЗ та ще більш потужне, у 4–9 разів, підвищення ризику розвитку ЦД 2-го типу, а за наявності цих захворювань відбувається дестабілізація їх перебігу. Наочною ілюстрацією впливу стресу військових дій на рівень глікемії є результати дослідження ізраїльських науковців. Продемонстровано, що в осіб, які мешкають в 7-кілометровій зоні сектора Газа, рівень глюкози крові достовірно вищий, ніж у населення більш віддалених від цього району територій. Автори роботи пов’язують це зі стресом, що зумовлений більшою частотою ракетних ударів та меншим проміжком часу, необхідного мешканцям цієї зони, щоб діста-тися укриття. Також встановлено, що довша тривалість військових операцій, незалежно від місця проживання, справляє негативний вплив на рівень глюкози крові. При цьому чим довша тривалість операції та більша інтенсивність ударів, тим більш високий рівень глікемії реєструється у населення регіону. Також встановлено, що саме пацієнти з діабетом є більш уразливими щодо підвищення рівня глікемії [7].

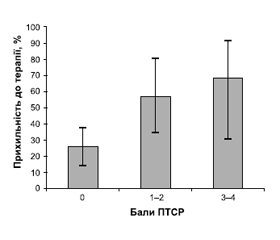

Обговорюючи вплив дистресу в умовах військового стану на перебіг та прогноз пацієнтів з АГ і ЦД 2-го типу, неможливо ігнорувати питання вчасної діагностики та лікування тривожних і депресивних розладів. Серед пацієнтів з резистентною АГ, значну частку яких становлять пацієнти з ЦД 2-го типу та хронічною хворобою нирок (ХХН), клінічно значущі симптоми депресії були діагностовані у 21 %, а тривоги — у 17 % [11]. Крім того, більш старший вік та жіноча стать є факторами ризику розвитку депресії та посттравматичного стресового розладу, які є незалежними чинниками ССЗ [15]. Депресія та тривога асоційовані зі зростанням ризику виникнення інфаркту міокарда, стенокардії й випадків серцево-судинної смерті. Так, у пацієнтів, які не мали в анамнезі атеросклеротичних ССЗ, наявність депресії підвищує частоту розвитку ішемічної хвороби серця (ІХС) у 1,3–1,5 раза, а тривога асоціюється з підвищенням ризику розвитку ІХС на 26–41 % та інших ССЗ — на 52 % [6]. При цьому не тільки патофізіологічні механізми прогресування атеросклерозу (підвищення активності САС і РААС, дисфункція ендотелію з активацією запалення низької градації, окиснювального стресу та посиленням агрегації тромбоцитів), а й поведінкові особливості (зниження прихильності до лікування або повна відмова від нього) сприяють зростанню ризику ССЗ. До того ж посттравматичний стресовий розлад (ПТСР) також є потенційним чинником розвитку АГ, ЦД та ССЗ. Ретроспективний аналіз даних 3846 військовослужбовців США, які набули травматичного досвіду в Афганістані та Іраку, продемонстрував поширеність у цій когорті ПТСР на рівні 42 %, АГ — 14,3 %. За результатами аналізу було встановлено, що тривалий ПТСР та тяжкість травми були незалежними пре-дикторами розвитку АГ [8].

Крім того, у дослідженні в пацієнтів з неконт-рольованою АГ ПТСР було визначено як фактор ризику неприхильності до лікування [3]. При цьому встановлено чіткий лінійний зв’язок між тяжкістю ПТСР та ступенем неприхильності до антигіпертензивної терапії (рис. 1).

Саме тому первинна діагностика депресивних, тривожних, посттравматичних стресових розладів у загальній терапевтичній практиці є сьогодні вельми актуальною.

Неналежний глікемічний контроль, неефективний контроль АТ і показників ліпідного спектра крові та несвоєчасна інтенсифікація лікування підвищують ризик мікро- та макросудинних CC-ускладнень, який в жодному разі не можна недооцінювати. За даними реєстру Discover Global Registry, в українській когорті пацієнтів із ЦД 2-го типу реальна поширеність мікро- та макросудинних ускладнень є значущою. Зокрема, ХХН наявна майже в половини пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу (47,1 %), серцева недостатність (СН) — більше ніж у половини (62,3 %).

Неефективний контроль глікемії та АТ є провідним чинником прогресування хронічної хвороби нирок. За умови відсутності контролю цих двох факторів прогресування ХХН до термінальної стадії відбувається досить швидко. Пацієнти з ХХН потребують постійного дієтологічного та фармакологічного лікування (з урахуванням ризику інфекцій сечовивідних шляхів і статевих органів). В умовах воєнного конфлікту пацієнти часто втрачають можливість своєчасної діагностики захворювання та моніторингу функціонального стану нирок (рШКФ), що підвищує ризик прогресування нефропатії, розвитку тяжких ускладнень і негативно впливає на час переходу до діалізу. Для надання пацієнтам ефективної комплексної допомоги ХХН має бути діагностована на ранніх стадіях, але обізнаність про цю хворобу та швидкість діагностики, на жаль, залишаються низькими. За даними масштабних зарубіжних досліджень, понад 70 % пацієнтів із ХХН 1–3-ї стадії не знають про своє захворювання, а ХХН 3-ї стадії залишається недостатньо діагностованою. При цьому на пізніх стадіях ХХН є мало можливостей відтермінувати її подальше прогресування й уникнути ускладнень.

Розуміння механізмів, які лежать в основі погіршення стану пацієнтів з АГ і ЦД в умовах дистресу, є ключем до вибору ефективної терапії, направленої на відновлення контролю АТ і глікемії та ефективне запобігання серцево-судинним та нирковим ускладненям.

Досягнення та утримання цільового АТ є необхідною умовою покращення прогнозу пацієнтів з АГ, а в поєднанні з ЦД 2-го типу це набуває ще більшої актуальності. Згідно з настановою Американської діабетичної асоціації (ADA) 2012 року, оновлений підхід до лікування пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу передбачає чотири стовпи: контроль рівнів глюкози, артеріального тиску, ліпідів і використання препаратів, що знижують рівень глюкози, які, як було показано, мають переваги для серця та нирок (рис. 2) [14].

/40_2.jpg)

Загальні підходи до терапії АГ у пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу суттєво не відрізняються з погляду кардіо-логічних та ендокринологічних товариств. Різниця стосується скоріше європейських та американських критеріїв визначення нижчого цільового АТ та підходів до ініціації терапії. В європейських настановах критерієм зниження АТ у межах 120–130/70–80 мм рт.ст. є вік до 70 років, тоді як в американських — ступінь ризику ССЗ: такого рівня АТ рекомендовано прагнути, якщо ризик високий і дуже високий. Щодо старту лікування, європейські настанови рекомендують комбіновану терапію [17], американські пропонують починати з монотерапії, якщо АТ знаходиться в межах 130–150/80–90 мм рт.ст. [14].

Для контролю АТ можна застосовувати будь-які препарати першої лінії (інгібітори АПФ (іАПФ), блокатори рецепторів ангіотензину (БРА), тіазидоподібні/тіазидні діуретики та дигідропіридинові блокатори кальцієвих каналів (БКК)). БРА й іАПФ рекомендовані як препарати першої лінії в пацієнтів зі значною альбумінурією (відношення альбумін/креатинін у сечі > 300 мг/г креатиніну), оскільки вони дають змогу знизити ризик прогресування захворювання нирок. Застосування цих класів слід також розглянути при помірній альбумінурії (відношення альбумін/креатинін у сечі — 30–299 мг/г креатиніну). При виборі другого та третього засобу мають братися до уваги такі чинники, як набряки, ШКФ, наявність СН й аритмій. Якщо відсутні чинники, які можуть впливати на вибір препарату, можна спиратися на дані дослідження ACCOMPLISH, які стверджують, що комбінація іАПФ + дигідропіридиновий БКК має перевагу над комбінацією іАПФ + тіазидний діуретик у зменшенні ризику ССЗ у пацієнтів із ЦД та без нього. У той же час у дослідженні ADVANCE отримано переконливі докази поліпшення прогнозу пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу під впливом комбінації іАПФ/тіазидоподібного діуретика (периндоприл/індапамід). Індапамід відносять до метаболічно нейтральних діуретиків, принаймні це стосується вуглеводного та ліпідного обміну. Існують застереження щодо застосування високих доз гідрохлортіазиду та хлорталідону, оскільки вони можуть сприяти зростанню рівня глюкози крові. Проте дози цих діуретиків, які використовуються сьогодні у складі фіксованих комбінацій, є безпечними з метаболічної точки зору.

Украй актуальним в умовах стресу є питання застосування блокаторів β-адренорецепторів у пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу. У сучасній концепції лікування АГ β-блокатори призначаються за наявності таких показань: перенесений інфаркт міокарда, стенокардія, СН, планування вагітності [17]. Вони також можуть бути патогенетичним вибором для лікування АГ за умов гіперсимпатикотонії, яка часто є супутником ЦД 2-го типу та підсилюється в умовах стресу. Більшість нарікань відноситься до неселективних β-адреноблокаторів, яким притаманні несприятливі метаболічні наслідки, проте високоселективні β1-адреноблокатори на кшталт бісопрололу або небівололу (має додаткові вазодилататорні властивості) не чинять впливу на показники вуглеводного та ліпідного метаболізму, а β-блокатор із α-блокуючими властивостями карведилол у дослідженні GEMINI продемонстрував здатність покращувати певні компоненти метаболічного синдрому, включаючи чутливість до інсуліну, в пацієнтів з АГ та ЦД 2-го типу.

Необхідність застосування фіксованих комбінацій антигіпертензивних препаратів у пацієнтів з АГ і ЦД 2-го типу не підлягає сумніву, зважаючи на кількість препаратів для щоденного застосування. Усі рекомендації також наголошують, що у разі неефективності подвійної комбінації інтенсифікація лікування полягає у використанні потрійної фіксованої комбінації, як правило, у складі блокатора РААС/діуретика/БКК. Якщо ж така комбінація в максимально переносимій дозі виявиться неефективною, буде йтися про резистентність до антигіпертензивної терапії [17].

Щодо тактики лікування пацієнтів із резистентною АГ, то дослідження PATHWAY-2 чітко продемонструвало перевагу спіронолактону над бісопрололом і доксазозином як четвертим препаратом для лікування. Варто зазначити, що 14 % учасників цього дослідження мали ЦД 2-го типу. У групі пацієнтів з резистентною АГ, обстежених у відділі АГ та коморбідної патології, частка пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу становила 24,4 %. Одним із потужних факторів формування резистентної АГ є прогресування ниркового ураження, тому відсоток резистентної АГ серед пацієнтів з ЦД напряму залежить від наявності та ступеня ХХН. Оскільки рандомізовані контрольовані дослідження щодо лікування резистентної АГ у пацієнтів із ЦД відсутні, після додавання спіронолактону вибір наступного кроку терапії ґрунтується виключно на експертній думці. П’ятим і далі препаратом може бути β-блокатор, α-адреноблокатор і препарати центральної дії, серед яких перевага надається агоністу імідазолінових рецепторі 1-го типу моксонідину.

При виборі комбінацій для лікування АГ мають братися до уваги й особливі характеристики гіпертензії в пацієнтів із ЦД. Насамперед це стосується порушень добового ритму АТ за типом non-dipper (недостатнє зниження АТ вночі) та night-peaker (середній нічний АТ є вищим за денний). Порушення добового ритму АТ розглядаються як додаткові несприятливі прогностичні фактори розвитку СС-ускладнень. Вони часто зустрічаються у пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу, і ще частіше за наявності ХХН. Одним із суттєвих чинників недостатнього зниження АТ вночі та нічної гіпертензії є порушення сну, які часто супроводжують стресові розлади, а в умовах війни зумовлені нічними сигналами тривоги та необхідністю переміщення в укриття під час них. Порушення сну мають окреме, самостійне значення як для розвитку тривожно-депресивних розладів, так і для посилення ризику ССЗ. Депривація сну тісно асоціюється з розвитком АГ, ІХС і ЦД, а підвищення активності САС разом зі змінами секреції мелатоніну розглядають як основні патофізіологічні механізми, що залучаються в прогресування ССЗ за умови недостатньої тривалості нічного сну. В основі порушень добового ритму АТ на тлі інсомнії та тяжких порушень сну лежать ті самі механізми, які супроводжують тривалий стрес: гіперактивація гіпоталамо-пітуїтарно-адреналової осі та гіперсекреція кортизолу. Крім того, певну роль може відігравати активація САС та імунозапальних процесів. Поодинокі клінічні дослідження продемонстрували покращення показників циркадного ритму АТ під впливом препаратів, які покращують якість сну. Так, небензодіазепіновий снодійний засоб золпідем сприяв конверсії добового ритму non-dipper в dipper, тобто зміні з недостатнього зниження АТ вночі на нормальний циркадний ритм [9]. Застосування інгібітору зворотного захвату серотоніну есциталопраму на додаток до антигіпертензивної терапії призвело до суттєвого покращення якості сну, зниження рівня тривоги та депресії та асоціювалося з більш значним зниженням офісного систолічного/діастолічного АТ порівняно з плацебо (–10,5/–8,1 проти –3,4/–2,7 мм рт.ст.; P < 0,001) [12].

Проте порушення добового ритму АТ у пацієнтів з АГ, ЦД та ХХН можуть мати місце не тільки при інсомнії. Автономний дисбаланс та гіперактивація РААС створюють умови для стійкого підвищення АТ не лише в денний, а й у нічний період. Саме це зумовлює потребу в застосуванні препаратів із тривалим антигіпертензивним ефектом упродовж 24 годин при одноразовому прийомі, який є бажаним із погляду зменшення кількості таблеток на добу. Це принципово важливо для пацієнтів із ЦД, у яких поліфармація — радше правило, ніж виняток, а використання фіксованих комбінацій із препаратами тривалої дії забезпечує контроль АТ удень та вночі, мінімізуючи загальну кількість таблеток на добу.

Цільовий рівень АТ у пацієнтів з ХХН дотепер залишається дискутабельним питанням. В останній європейській настанові з профілактики ССЗ [16] рекомендовано зниження офісного САТ у межах 130–139 мм рт.ст., натомість в настанові KDIGO 2021 року з лікування АГ у пацієнтів з ХХН як мету зазначено САТ < 120 мм рт.ст. за даними стандартизованого офісного вимірювання АТ [4]. Варто зазначити, що стандартизоване вимірювання проводиться в офісі лікаря, але за повної відсутності медичного персоналу. Тому результати таких вимірювань можуть бути нижчими, ніж звичайних офісних. Щодо особливостей антигіпертензивної терапії за наявності ХХН, вони стосуються обмежень, пов’язаних із призначенням препаратів, які здатні підвищувати сироватковий рівень калію, якщо є схильність до гіперкаліємії. До них відносяться блокатори РААС, але більшою мірою антагоністи мінералокортикоїдних рецепторів. Вибір діуретика у пацієнтів з ХХН залежить від ШКФ. При ШКФ < 30 мл/хв/1,73 м2 перевага надається петльовим діуретикам. Інші принципи антигіпертензивної терапії суттєво не відрізняються від лікування інших категорій пацієнтів з АГ, проте, як вже зазначалося, значна частина пацієнтів з ХХН має резистентний перебіг АГ і потребує індивідуалізованої багатокомпонентної терапії.

Окрім того, призначаючи антигіпертензивну терапію пацієнтам з ЦД, потрібно враховувати антигіпертензивний ефект інгібіторів натрійзалежного котранспортера глюкози 2-го типу (іНЗКТГ-2), який у середньому становить 3–5 мм рт.ст. Водночас варто зважати на те, що чим вищим є вихідний АТ, тим більшого його зниження можна очікувати при застосуванні препаратів. Як вже зазначалося, досягнення й утримання цільового рівня АТ поряд із адекватною статинотерапією та застосуванням цукрознижувальних препаратів з доведеним впливом на кардіоренальний прогноз (іНЗКТГ-2, агоністи рецепторів глюкагоноподібного пептиду 1 (арГПП-1)) є запорукою зниження ризику розвитку серцево-судинних і ниркових ускладнень.

Останнім часом було отримано чимало нових доказів позитивного впливу вищезгаданих класів цукрознижувальних препаратів на прогноз пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу. Вплив іНЗКТГ-2 та арГПП-1 на жорсткі СС та ниркові кінцеві точки був продемонстрований у пацієнтів з ЦД 2-го типу високого та дуже високого СС-ризику, з ХХН і СН. Саме тому у настанові ADA 2022 року для цих категорій пацієнтів було розроблено окремий алгоритм цукрознижувальної терапії (рис. 3) [14].

Застосування іНЗКТГ-2 рекомендується не лише для лікування СН зі зниженою фракцією викиду, на сьогодні їх застосування рекомендоване для лікування та профілактики інших типів СН, зважаючи на результати досліджень 2021 року. За рекомендаціями ADA 2022 року, поєднання препаратів з груп іНЗКТГ і арГПП-1 слід розглядати, щоб ще більше знизити ризик ускладнень ЦД 2-го типу.

Як вже зазначалося, приєднання ХХН є суттєвим негативним фактором прогнозу пацієнтів з АГ і ЦД. У 2022 році міжнародним товариством нефрологів KDIGO були розроблені та опубліковані Клінічні практичні рекомендації щодо лікування ЦД при ХХН [5]. Вони передбачають заходи, які можна наочно подати у вигляді піраміди, що складається з 3 ключових рівнів (рис. 4).

Принципи лікування включають заходи щодо модифікації способу життя, які лежать в основі терапії всіх хронічних неінфекційних захворювань. Вони передбачають медикаментозну терапію першої лінії, до якої відносяться метформін, іНЗКТГ-2, блокатори РААС і статини, а також додаткову терапію, направлену на досягнення цільових рівнів глікемії, АТ, ЛПНЩ, та застосування за показаннями антитромботичних препаратів, арГПП-1 і нестероїдних антагоністів мінералокортикоїдних рецепторів (препарат фінеренон, який зараз в Україні поки що не зареєстрований).

Оновлені рекомендації ADA та KDIGO 2022 року, ґрунтуючись на результатах останніх досліджень, дозволили використання іНЗКТГ-2 з нефропротекторною метою у пацієнтів з ХХН 4-ї стадії, якщо ШКФ не нижче 30 мл/хв [14, 5]. Експерти припускають, що більше людей на прогресивних стадіях ХХН можуть безпечно використовувати іНЗКТГ-2 для сповільнення прогресування ХХН.

Підсумовуючи вищевикладене, варто акцентувати увагу на відновленні адекватної комплексної терапії пацієнтів з АГ, ЦД 2-го типу та ХХН в умовах стресу на тлі війни. Вчасне виявлення дестабілізації кардіометаболічних та ренальних захворювань, ефективний контроль факторів ризику, застосування прогнозмодифікуючих препаратів та діагностика і лікування ПТСР, тривожних і депресивних розладів сприятимуть покращенню прогнозу коморбідних пацієнтів з АГ, ЦД 2-го типу та ХХН.

Конфлікт інтересів. Автори заявляють про відсутність конфлікту інтересів та власної фінансової зацікавленості при підготовці даної статті.

Отримано/Received 15.07.2022

Рецензовано/Revised 27.07.2022

Прийнято до друку/Accepted 09.08.2022

Список литературы

1. Дослідження STEPS: поширеність факторів ризику неінфекційних захворювань в Україні у 2019 році. Копенгаген: Європейське регіональне бюро ВООЗ, 2020. Ліцензія: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

2. Коваленко В.Н., Лутай М.И., Митченко Е.И., Пархоменко А.Н., Сиренко Ю.Н. и др. Стресс и сердечно-сосудистые заболевания. Здоров’я України. 2015. № 8 (357). С. 38-39.

3. Burg M.M., Brandt C., Buta E., et al. Risk for Incident Hypertension Associated with PTSD in Military Veterans, and The Effect of PTSD Treatment. Psychosom. Med. 2017. 79(2). 181-188. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000376.

4. Cheung A.K., Chang T.I., Cushman W.C. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International. 2021. 99. 559-569.

5. Eknoyan G., Lameire N., et al. KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Mangement in Chronic Kidney Di-sease [Internet]. https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/KDIGO-2022-Diabetes-Management-GL_Public-Review-draft_1Mar2022.pdf.

6. Emdin C.A., Odutayo A., Wong C.X., et al. Meta-analysis of anxiety as a risk factor of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016. 118. 511-519.

7. Hackett R.A., Steptoe A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and psychological stress — a modifiable risk factor. Nature Reviews Endocrino-logy. 2017. 13. 547-560. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo. 2017.64.

8. Howard J.T., Sosnov J.A., Janak J.C., et al. Associations of Initial Injury Severity and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Diagnoses with Long-Term Hypertension Risk after Combat Injury. Hypertension. 2018. 71. 824-832. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10496.

9. Huang Y., Mai W., Cai X., et al. The effect of zolpidem on sleep quality, stress status, and nondipping hypertension. Sleep Med. 2012. 13. 263-268.

10. Inoue K., Horwich T., Bhatnagar R., et al. Urinary Stress Hormones, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Events: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2021. 78. 1640-1647. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17618.

11. Lenski D., Kindermann I., Anxiety L., Depression, quality of life and stress in patients with resistant hypertension before and after catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation. Eurointervention. 2013. 9. 700-708.

12. Li Y., Yang Y., Li Q., et al. The impact of the improvement of insomnia on blood pressure in hypertensive patients. J. Sleep Res. 2017. 26. 105-114.

13. Rozansky A. Psychosocial risk factors and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, screening, and treatment considerations. Cardiovasc. Innov. Applications. 2016. 1. 417-431.

14. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes — 2022. Diabetes Care. 2022. 45(Suppl. 1). S1-S2.

15. Vaccarino V., Goldberg J., Rooks C., et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: a twin study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013. 62. 970-978.

16. Visseren F.L.J., Mach F., Smulders Y.M. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. European Heart Journal. 2021. 00. 1-111. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484.

17. Williams B., Mancia G., Spiering W., et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). Eur. Heart J. 2018. 39(33). 3021-104. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339.

/40.jpg)

/39.jpg)

/40_2.jpg)

/43.jpg)