Международный неврологический журнал Том 20, №4, 2024

Вернуться к номеру

Вплив анатомічного рівня ушкодження спинного мозку на ступінь вираженості неврологічних порушень при хребетно-спинномозковій травмі

Авторы: Нехлопочин О.С., Никифорова А.М., Вербов В.В., Йовенко Т.А., Чешук Є.В.

ДУ «Інститут нейрохірургії імені академіка А.П. Ромоданова НАМН України», м. Київ, Україна

Рубрики: Неврология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

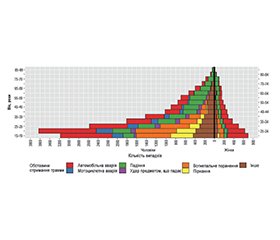

Актуальність. Травматичне ушкодження спинного мозку (СМ) є важливою медико-соціальною проблемою. Незважаючи на велику кількість досліджень, значного успіху щодо зменшення неврологічних наслідків у таких пацієнтів не досягнуто, а низку аспектів мало вивчено, зокрема реакцію СМ на травму за різних анатомічних рівнів ушкодження. Мета: використовуючи найбільшу з загальнодоступних баз даних пацієнтів із травматичними ушкодженнями СМ, проаналізувати вплив анатомічного рівня ушкодження, статі постраждалого й механізму отримання травми на патерн функціональних розладів у гострий період хребетно-спинномозкової травми. Матеріали та методи. Проведено статистичний аналіз даних з National Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems Database (версія 2021 ARPublic). Для аналізу відібрано 21 343 випадки, що містять інформацію про стать, вік на момент травми, обставини отримання травми, ступінь неврологічних розладів при госпіталізації й анатомічний рівень травматичного ушкодження (до сегмента СМ). Результати. При аналізі даних виявлено значні відмінності за патерном розподілу функціональних класів за шкалою ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) залежно від анатомічного рівня ушкодження СМ. Так, для шийного відділу розподіл частот класів A, B, C і D був таким: 43,06 % (95% довірчий інтервал (ДІ) 42,15–43,97 %), 14,99 % (95% ДІ 14,35–15,66 %), 16,17 % (95% ДІ 15,50–16,86 %) та 25,78 % (95% ДІ 24,98–26,59 %) відповідно, для грудного відділу — 70,97 % (95% ДІ 69,94–71,97 %), 10,27 % (95% ДІ 9,60–10,97 %), 9,92 % (95% ДІ 9,26–10,61 %) та 8,85 % (95% ДІ 8,23–9,51 %), для поперекового відділу — 21,29 % (95% ДІ 19,57–23,12 %), 15,87 % (95% ДІ 14,35–17,52 %), 24,43 % (95% ДІ 22,62–26,34 %) і 38,40 % (95% ДІ 36,32–40,52 %). Висновки. Патерн розподілу функціональних класів неврологічних порушень значною мірою залежить від анатомічного рівня ушкодження СМ. Ушкодження грудних сегментів СМ демонструє клінічно найтяжчу симптоматику, ушкодження поперекових сегментів — найменш виражену. Стать постраждалого не має статистично значущого впливу, тоді як обставини отримання травми корелюють із частотою неврологічних порушень при ушкодженні шийних сегментів і не впливають на цей показник у поперековому відділі.

Background. Traumatic spinal cord injury is a significant medical and social issue. Despite numerous studies, substantial success in reducing neurological consequences in such patients has not yet been achieved, and several aspects remain understudied, particularly the response of the spinal cord to injury at different anatomical levels. The purpose is to analyze the influence of the anatomical level of injury, the patient’s gender, and the mechanism of injury on the pattern of functional disorders in the acute period of spinal cord trauma using the largest publicly available database of patients with traumatic spinal cord injuries. Materials and methods. A statistical analysis of data from the National Spinal Cord Injury Model Systems Database (version 2021 ARPublic) was conducted. It included 21,343 cases containing information on gender, age at the time of injury, circumstances of injury, the degree of neurological disorders at hospitalization, and the anatomical level of traumatic injury (with precision down to the spinal cord segment). Results. The data analysis revealed significant differences in the pattern of distribution of functional classes according to the American Spinal Injury Association scale depending on the anatomical level of spinal cord injury. For the cervical region, the distribution of frequencies for A, B, C, and D classes was as follows: 43.06 % (95% confidence interval (CI): 42.15–43.97 %), 14.99 % (95% CI: 14.35–15.66 %), 16.17 % (95% CI: 15.50–16.86 %) and 25.78 % (95% CI: 24.98–26.59 %), respectively, for the thoracic region — 70.97 % (95% CI: 69.94–71.97 %), 10.27 % (95% CI: 9.60–10.97 %), 9.92 % (95% CI: 9.26–10.61 %) and 8.85 % (95% CI: 8.23–9.51 %), for the lumbar region — 21.29 % (95% CI: 19.57–23.12 %), 15.87 % (95% CI: 14.35–17.52 %), 24.43 % (95% CI: 22.62–26.34 %) and 38.40 % (95% CI: 36.32–40.52 %). Conclusions. The pattern of distribution of functional classes of neurological impairments significantly depends on the anatomical level of spinal cord injury. Thoracic segment injuries are characterized by the most clinically severe symptoms, whereas lumbar segment injuries are the least severe. The patient’s gender does not have a statistically significant influence, while the circumstances of the injury correlate with the frequency of neurological impairments in cervical segments and do not affect this indicator in the lumbar region.

травматичне ушкодження спинного мозку; анатомічний рівень ушкодження; функціональні розлади; стать потерпілого; механізм травми; неврологічні порушення

traumatic spinal cord injury; anatomical level of injury; functional disorders; patient gender; mechanism of injury; neurological impairments