Международный неврологический журнал Том 21, №1, 2025

Вернуться к номеру

Дослідження частоти виникнення та ознак посттравматичного стресового розладу на етапі первинної медичної допомоги у військовослужбовців і вимушено переміщених осіб під час повномасштабного вторгнення

Авторы: Масік Н.П., Килимчук В.В., Масік О.І., Матвійчук М.В., Мазур О.І., Тереховська О.І., Барабаш І.Л.

Вінницький національний медичний університет ім. М.І. Пирогова, м. Вінниця, Україна

Рубрики: Неврология

Разделы: Клинические исследования

Версия для печати

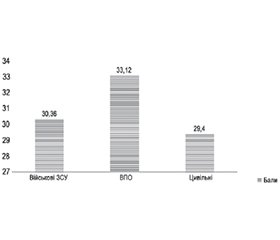

Актуальність. Війна та її наслідки не лише виходять на перший план колективної й національної свідомості кожного громадянина, але й, як стресовий фактор, призводять до емоційного напруження та виснаження і є основним чинником стрес-асоційованих розладів, зокрема посттравматичного стресового розладу (ПТСР). Діагностика ПТСР ґрунтується на наявності хоча б одного з симптомів: інтрузії, уникання, негативного настрою та когнітивних порушень, гіперреактивності. Мета: дослідити частоту і тяжкість імовірного ПТСР серед пацієнтів, які відвідують лікарні первинної медичної допомоги (ПМД), військовослужбовців і вимушено переміщених осіб із застосуванням різних опитувальників. Матеріали та методи. Обстежено 90 осіб (46 чоловіків і 44 жінки середнього віку 39,65 ± 13,93 року). Пацієнтів розподілили (по 30 осіб) на три групи: І — військовослужбовці ЗСУ, які лікувались у КНП «ВМКЛ ШМД», ІІ — внутрішньо переміщені особи, які вимушено проживають у м. Вінниці (ВПО), та ІІІ — контрольна: цивільні мешканці м. Вінниці, які відвідували лікаря ПМД. Усім респондентам проводили анкетування за шкалою тривоги Спілбергера — Ханіна, визначали ймовірність виникнення ПТСР, використовуючи опитувальник для скринінгу ПТСР, затверджений МОЗ України 23.02.2024 р. № 1265, застосовували шкалу для оцінки ПТСР згідно з класифікацією DSM-5 (PCL-5). Результати. Ймовірний ПТСР частіше виявлявся у ВПО (83,33 % за шкалою скринінгу ПТСР і 56,67 % за шкалою PCL-5) порівняно з військовослужбовцями (53,33 і 40,0 % відповідно) та цивільними особами (10,0 і 3,33 % відповідно). Причому у ВПО переважали симптоми уникання (76,67 %), негативного пізнання (76,67 %) та гіперзбудження (88,33 %), що підкреслює вагому роль емоційних реакцій і можливий вплив на інші симптоми ПТСР. Встановлені кореляційні зв’язки (p < 0,05) між віком, статтю і кількістю балів за шкалою PCL-5. Висновки. Ймовірний ПТСР можна успішно встановити за допомогою будь-якого інструменту (скринінгу ПТСР, PCL-5) з практично однаковою частотою, що дозволяє виявити контингент осіб, які повинні бути направлені на додаткове обстеження щодо підтвердження ПТСР із подальшим лікуванням цього стану.

Background. War and its consequences not only dominate the collective and national consciousness of every citizen but also, as a stressor, lead to emotional tension and exhaustion. They are a major factor in stress-associated disorders, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The diagnosis of PTSD is based on the presence of at least one symptom: intrusion, avoidance, negative mood and cognitive impairments, hyperreactivity. The purpose was to investigate the prevalence and severity of probable PTSD among patients visiting primary health care (PHC) facilities, military personnel, and forcibly displaced people (FDP) using various questionnaires. Materials and methods. A total of 90 individuals (46 men and 44 women, average age 39.65 ± 13.93 years) were examined. Participants were divided into three groups (30 individuals each): group I — military personnel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine receiving treatment at the Municipal Non-Profit Enterprise “Vinnytsia City Clinical Emergency Hospital”; group II — internally displaced persons who are forced to live in Vinnytsia (FDP); group III — controls (civilian residents of Vinnytsia visiting PHC facilities). All respondents were surveyed using the Spielberg-Hanin Anxiety Scale, assessed for the likelihood of PTSD using a PTSD screening questionnaire approved by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine (Order No. 1265 dated February 23, 2024), and with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Results. Probable PTSD was more frequently detected among FDP (83.33 % on the PTSD screening scale and 56.67 % on the PCL-5) compared to military personnel (53.33 and 40.0 %, respectively) and civilians (10.0 and 3.33 %, respectively). Among FDP, symptoms of avoidance (76.67 %), negative cognition (76.67 %), and hyperarousal (88.33 %) were predominant, emphasizing the significant role of emotional responses and their potential impact on other PTSD symptoms. Correlations (p < 0.05) were found between age, gender, and the score on the PCL-5. Conclusions. Probable PTSD can be successfully detected using any of the available tools (PTSD screening, PCL-5) with almost equal frequency, allowing for the identification of individuals who should undergo additional examination for PTSD confirmation and subsequent treatment of this condition.

посттравматичний стресовий розлад; скринінг; військовий стан; військовослужбовці; вимушено переміщені особи; первинна медична допомога

post-traumatic stress disorder; screening; martial law; military personnel; forcibly displaced people; primary health care

Для ознакомления с полным содержанием статьи необходимо оформить подписку на журнал.

- 1. Рання діагностика стрес-асоційованих невротичних розладів. За матеріалами ІІ Міжнародного конгресу «Family DOC congress» (7–8 квітня 2023 р.). Neuronews. 2023;8(144):8-12. Available from: https://neuronews.com.ua/uploads/issues/2023/8(144)/nn23_8_8-12.pdf. Ukrainian.

- 2. Chorna V, Serebrennikova O, Kolomiets V, Hozak S, Yelizarova O, Rybinskyi M, Anhelska V, Pavlenko N. Posttraumatic stress disorder during full-scale war in military personnel. Young Scientist. 2023;12(124):28-39. Available from: https://doi.org/10.32839/2304-5809/2023-12-124-28. Ukrainian.

- 3. Megnin-Viggars O, Mavranezouli I, Greenberg N, Hajioff S, Leach J. Post-traumatic stress disorder: what does NICE guidance mean for primary care? Br J Gen Pract. 2019 Jul;69(684):328-329. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704189. PMID: 31249072; PMCID: PMC6592320.

- 4. Schäfer SK, Kunzler AM, Lindner S, Broll J, Stoll M, Stoffers-Winterling J, Lieb K. Transdiagnostic psychosocial interventions to promote mental health in forcibly displaced persons: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023;14(2):2196762. doi: 10.1080/20008066.2023.2196762. PMID: 37305944; PMCID: PMC10262817.

- 5. Wu Y, Wang L, Tao M, Cao H, Yuan H, Ye M, Chen X, Wang K, Zhu C. Changing trends in the global burden of mental disorders from 1990 to 2019 and predicted levels in 25 years. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2023 Nov 7;32:e63. doi: 10.1017/S2045796023000756. PMID: 37933540; PMCID: PMC10689059.

- 6. Romanova OM, Srybna OV, Sychov OS. New opportunities for optimizing the treatment of supraventricular heart rhythm disorders in patients with arterial hypertension under conditions of chronic stress. Ukrainian Therapeutic Journal. 2023;4:40-48. http://doi.org/10.30978/UTJ2023-4-40. Ukrainian.

- 7. Kolesnikova OV, Zaprovalna OY, Yemelianova NY, Radchenko AO, Galchinska VY. Impact of wartime stress factors on the metabolic status of the civilian population. Ukrainian Therapeutic Journal. 2023;3:37-43. http://doi.org/10.30978/UTJ2023-3-37. Ukrainian.

- 8. GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022 Feb;9(2):137-150. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. Epub 2022 Jan 10. PMID: 35026139; PMCID: PMC8776563.

- 9. Уніфікований клінічний протокол первинної та спеціалізованої медичної допомоги (УКПМД) «Гостра реакція на стрес. Посттравматичний стресовий розлад. Порушення адаптації». 2024 р. Посилання: https://www.dec.gov.ua/cat_mtd/galuzevi-standarti-ta-klinichninastanovi/. Ukrainian.

- 10. PTSD: National Center for PTSD 2021. Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp.

- 11. Chambliss T, Hsu J-L, Chen M-L. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in Veterans: A Concept Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2024;14:485. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060485.

- 12. Weinstein N, Khabbaz F, Legate N. Enhancing need satisfaction to reduce psychological distress in Syrian refugees. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016 Jul;84(7):645-50. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000095. Epub 2016 Mar 28. PMID: 27018533.

- 13. Priebe S, Giacco D, El-Nagib R. Public health aspects of mental health among migrants and refugees: A review of the evidence on mental health care for refugees, asylum seekers and irregular migrants in the WHO European Region. In Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK391045/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- 14. Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whi-teford H, Saxena S. New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019 Jul 20;394(10194):240-248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1. Epub 2019 Jun 12. PMID: 31200992; PMCID: PMC6657025.

- 15. Specker P, Liddell BJ, O’Donnell M, Bryant RA, Mau V, McMahon T, Byrow Y, & Nickerson A. The Longitudinal Association Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Emotion Dysregulation, and Postmigration Stressors Among Refugees. Clinical Psychological Science. 2024;12(1):37-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/21677026231164393.

- 16. Halych M, Lytvyn V. General Characteristics of the Post-Traumatic Stress Schedule in War-Time Conditions: Diagnosis and Prevention. Ûridična psihologìâ. 2022;1(30):22-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.33270/03223001.22. Ukrainian.

- 17. World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 2018. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (accessed on 7 Jun 2019).

- 18. Punski-Hoogervorst JL, Engel-Yeger B, Avital A. Attention deficits as a key player in the symptomatology of posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2023;101:1068-1085. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.25177.

- 19. Cowlishaw S, Metcalf O, Stone C, O'Donnell M, Lotzin A, Forbes D, Hegarty K, Kessler D. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Primary Care: A Study of General Practices in England. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021 Sep;28(3):427-435. doi: 10.1007/s10880-020-09732-6. PMID: 32592119; PMCID: PMC7318731.

- 20. Hori H, Kim Y. Inflammation and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019 Apr;73(4):143-153. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12820. Epub 2019 Feb 21. PMID: 30653780.

- 21. Quinones MM, Gallegos AM, Lin FV, et al. Dysregulation of inflammation, neurobiology, and cognitive function in PTSD: an integrative review. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2020;20:455-480. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-020-00782-9.

- 22. Varyvoda K. Neurobiological and psychological aspects of post-traumatic stress disorder: analytical review. Scientia et Societus. 2022;2:101-107. doi: 10.31470/2786-6327/2022/2/101-107. Ukrainian.

- 23. Naegeli C, Zeffiro T, Piccirelli M, Jaillard A, Weilenmann A, Hassanpour K, Schick M, Rufer M, Orr SP, Mueller-Pfeiffer C. Locus Coeruleus Activity Mediates Hyperresponsiveness in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2018 Feb 1;83(3):254-262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.021. Epub 2017 Sep 7. PMID: 29100627.

- 24. Al Jowf GI, Snijders C, Rutten BP, de Nijs L, & Eijssen LMT. The Molecular Biology of Susceptibility to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Highlights of Epigenetics and Epigenomics. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22(19):10743. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910743.

- 25. Dunlop BW, Wong A. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in PTSD: Pathophysiology and treatment interventions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019 Mar 8;89:361-379. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.10.010. Epub 2018 Oct 17. PMID: 30342071.

- 26. Obuobi-Donkor G, Oluwasina F, Nkire N, Agyapong VIO. A Scoping Review on the Prevalence and Determinants of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Military Personnel and Firefighters: Implications for Public Policy and Practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jan 29;19(3):1565. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031565. PMID: 35162587; PMCID: PMC8834704.

- 27. Wall PH, Convoy SP, Braybrook CJ. Military Service-Related Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: Finding a Way Home. Nurs Clin North Am. 2019 Dec;54(4):503-515. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2019.08.008. Epub 2019 Oct 11. PMID: 31703776.

- 28. Friedman JK, Taylor BC, Hagel Campbell E, Allen K, Bangerter A, Branson M, Bronfort G, Calvert C, Cross L, Driscoll M, Evans R, Ferguson JE, Haley A, Hennessy S, Meis LA, Burgess DJ. Gender differences in PTSD severity and pain outcomes: baseline results from the LAMP trial. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Oct 15:2023.10.13.23296998. doi: 10.1101/2023.10.13.23296998. Update in: PLoS One. 2024 May 16;19(5):e0293437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0293437. PMID: 37873176; PMCID: PMC10593051.

- 29. McAndrew LM, Lu SE, Phillips LA, Maestro K, Quigley KS. Mutual maintenance of PTSD and physical symptoms for Vete-rans returning from deployment. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019 May 21;10(1):1608717. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1608717. PMID: 31164966; PMCID: PMC6534228.

- 30. Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess. 2016. Nov;28(11):1379-91.

- 31. Bovin MJ, Kimerling R, Weathers FW, Prins A, Marx BP, Post EP, & Schnurr PP. Diagnostic accuracy and acceptability of the Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) among US Veterans. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(2):e2036733. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36733.

- 32. Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, Marx BP, Kimerling R, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Kaloupek DG, Schnurr PP, Kaiser AP, Leyva YE, Tiet QQ. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): Development and Evaluation Within a Veteran Primary Care Sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 Oct;31(10):1206-11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5. Epub 2016 May 11. PMID: 27170304; PMCID: PMC5023594.

- 33. LeardMann CA, McMaster HS, Warner S, Esquivel AP, Porter B, Powell TM, Tu XM, Lee WW, Rull RP, Hoge CW; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Comparison of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Instruments From Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition vs Fifth Edition in a Large Cohort of US Military Service Members and Veterans. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Apr 1;4(4):e218072. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8072. PMID: 33904913; PMCID: PMC8080232.

- 34. Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Lewis CE, Downes AJ, Bisson JI. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 in a sample of trauma exposed mental health service users. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021 Jan 26;12(1):1863578. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1863578. PMID: 34992744; PMCID: PMC8725778.

- 35. Schlechter P, Hellmann JH, McNally RJ, Morina N. The longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in war survivors: Insights from cross-lagged panel network analyses. J Trauma Stress. 2022 Jun;35(3):879-890. doi: 10.1002/jts.22795. Epub 2022 Jan 14. PMID: 35030294; PMCID: PMC9303894.

- 36. Schlechter P, Hellmann JH, Morina N. Unraveling specifics of mental health symptoms in war survivors who fled versus stayed in the area of conflict using network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021 Jul 1;290:93-101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.072. Epub 2021 May 1. PMID: 33993086.

- 37. Bryant RA, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. The course of symptoms over time in people with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Trauma. 2024 Jun 20. doi: 10.1037/tra0001710. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38900517.