Международный неврологический журнал Том 21, №5, 2025

Вернуться к номеру

Типи вушних шумів (огляд літератури)

Авторы: S.K. Byelyavsky (1), V.I. Lutsenko (2), K.F. Trinus (1, 4), M.A. Trishchynska (3), O.Ye. Kononov (3)

(1) - Kyiv City Clinical Hospital for War Veterans, Kyiv, Ukraine

(2) - Institute of Otolaryngology named after O.S. Kolomiychenko of NAMSU, Kyiv, Ukraine

(3) - Shupyk National Healthcare University of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine

(4) - Interregional Academy for Staff Management, Kyiv, Ukraine

Рубрики: Неврология

Разделы: Справочник специалиста

Версия для печати

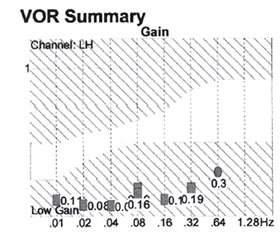

Bушні шуми вражають до 40 % населення західних країн. У цілому 1–3 % населення повідомляють про значне зниження якості життя внаслідок шуму у вухах через його вплив на сон і настрій. Вушні шуми — це тягар для системи охорони здоров’я, їхня частота в останні роки зростає. Популяційні дослідження надають важливі докази, підкреслюючи необхідність подальших робіт для вирішення проблем ефективної діагностики та клінічного лікування цього гетерогенного стану. Обговорення ведеться на основі класифікації Клауссена та Шульмана щодо чотирьох основних типів вушних шумів: тип I — шум (об’єктивний), тип II — ендогенний шум у вухах (суб’єктивний маскований), тип III — екзогенний вушний шум (суб’єктивний немаскований), тип IV — синдром повільної дегенерації стовбура мозку. Тип I: a) пульсуючий шум у вухах. Може мати багато причин; аневризма є найнебезпечнішим станом. Мітральна недостатність, звуки в скронево-нижньощелепному суглобі можуть бути пов’язані з пульсуючим вушним шумом; б) непульсуючий або періо-дичний: склероз судин. Непульсуючий або періодичний отосклероз (чи отоспонгіоз) — це ідіопатичний інфільтративний процес кам’янистої частини скроневої кістки, що може супроводжувати вушний шум. Найбільш поширеним типом є фенестральний отосклероз (85 %), який проявляється кондуктивною втратою слуху. У попередньому дослідженні етідронат виявився ефективним засобом лікування нейроотологічних симптомів отосклерозу. Тип II, суб’єктивний маскований. Нейросенсорне зниження слуху (периферичне) може мати кілька причин: порушення внутрішніх волоскових клітин, зовнішніх волоскових клітин (ЗВК), слуховий неврит, акустична невринома. Виявлення ролі внутрішніх волоскових клітин, ЗВК і слухових нейронів у розбірливости мови в тиші та за наявності фонового шуму зараз є гарячою темою в науковому співтоваристві. У попередніх дослідженнях продемонстровано, що слуховий нерв (СН) може відігравати певну роль у розумінні мовлення за наявності фонового шуму. Kujawa S.G., Liberman M.C. (2009) показали, що вплив шуму спричиняє тимчасове пошкодження ЗВК (вимірюють за отоакустичною емісією на частоті продукту спотворення) і постійне пошкодження СН (оцінюють за зменшенням амплітуди I хвилі слухової відповіді стовбура мозку). Ці результати свідчать про те, що ЗВК та СН сприяють розпізнаванню мови за наявності фонового шуму. Однак пошкодження ЗВК може відігравати основну роль у проблемах зі слухом у цій складній ситуації прослуховування. Тип III, суб’єктивний немаскований (із гіперакузією), переважно центральний. Багато людей із вушним шумом також страждають від гіперакузії. Як клінічні, так і основні наукові дані вказують на збіг патофізіологічних механізмів. В одному дослідженні 935 (55 %) із 1713 пацієнтів були охарактеризовані як хворі з гіперакузією. Гіперакузія при вушному шумі пов’язана з молодшим віком, вищим рівнем стресу, зумовленого шумом у вухах, психічним та загальним дистресом, більшою поширеністю больових розладів і запаморочення. Блокатори Н1 гістамінових рецепторів, Са каналів і мускаринові блокатори здаються ефективними. Тип IV, cиндром повільної дегенерації стовбура мозку. Етіологія: похилий вік, тяжка травма голови, отруєння, нервові інфекції. Прояви: запаморочення, емоційні розлади, когнітивні порушення, вушні шумі та головний біль.

Tinnitus affects up to 40 % of the population in Western countries. One to three percent of the general populations report a significant reduction in their quality of life due to tinnitus through its effect on sleep and mood. Tinnitus presents a burden to the health care system that has been rising in recent years. Population-based studies provide crucial underpinning evidence, highlighting the need for further research to address issues around effective diagnosis and clinical management of this heterogeneous condition. The discussion is done on the basis of Claussen and Shulman classification of the four main groups of tinnitus types: type I — bruit (objective), type II — endogenous tinnitus (subjective maskable), type III — exogenous tinnitus (subjective non-maskable), type IV — slow brainstem degeneration syndrome. Type I: a) pulsatile tinnitus. It can have many causes; aneurism is the most dangerous condition. Mitral insufficiency, temporomandibular joint sounds may be associated with pulsatile tinnitus; b) non-pulsatile (or periodical): vessel sclerosis. Non-pulsatile, or periodical, otosclerosis (otospongiosis) is an idiopathic infiltrative process of the petrous temporal bone that may present with tinnitus. The most common type is fenestral otosclerosis (85 %), which is associated with conductive hearing loss. In a preliminary study, etidronate appeared to be an effective treatment for the neurootologic symptoms of otosclerosis. Type II, subjective maskable. Sensory neural hearing decrease (peripheral) might have several causes: disorder of the inner hair cells, outer hair cells (OHCs), acoustic neuritis, acoustic neurinoma. Discovering the roles of inner hair cells, OHCs, and auditory neurons in speech understanding in quiet and in the presence of background noise is currently a hot topic in the scientific community. Previous studies have suggested that the auditory nerve (AN) may play a role in speech understanding in the presence of background noise. S.G. Kujawa, M.C. Liberman (2009) have shown that noise exposure causes temporary damage to OHCs (as measured by distortion product otoacoustic emissions) and permanent damage to the AN (measured by a decrease in the wave I amplitude of the auditory brainstem response). These preliminary results suggest that both OHCs and the AN contribute to speech recognition in the presence of background noise. However, OHC damage may play a primary role in hearing difficulties in this complex listening situation. Type III, subjective non-maskable (with hyperacusis), mostly central. Many people with tinnitus also suffer from hyperacusis. Both clinical and basic scientific data indicate an overlap in pathophysiologic mechanisms. In a study, 935 (55 %) out of 1713 people were characterized as hyperacusis patients. Hyperacusis in tinnitus was associated with younger age, higher tinnitus-related, mental and general distress, and higher rates of pain disorders and vertigo. Blockers of H1 histaminic receptors, Ca channels and muscarinic blockers seem to be effective. Type IV, slow brainstem degeneration syndrome. Etiology: old age, severe head trauma, poisoning, neural infections. Manifestations: dizziness, emotional disturbances, cognitive impairment, tinnitus and headaches.

шум у вухах; тинітус; об’єктивний та суб’єк-тивний шум у вухах

tinnitus; bruit; objective and subjective tinnitus